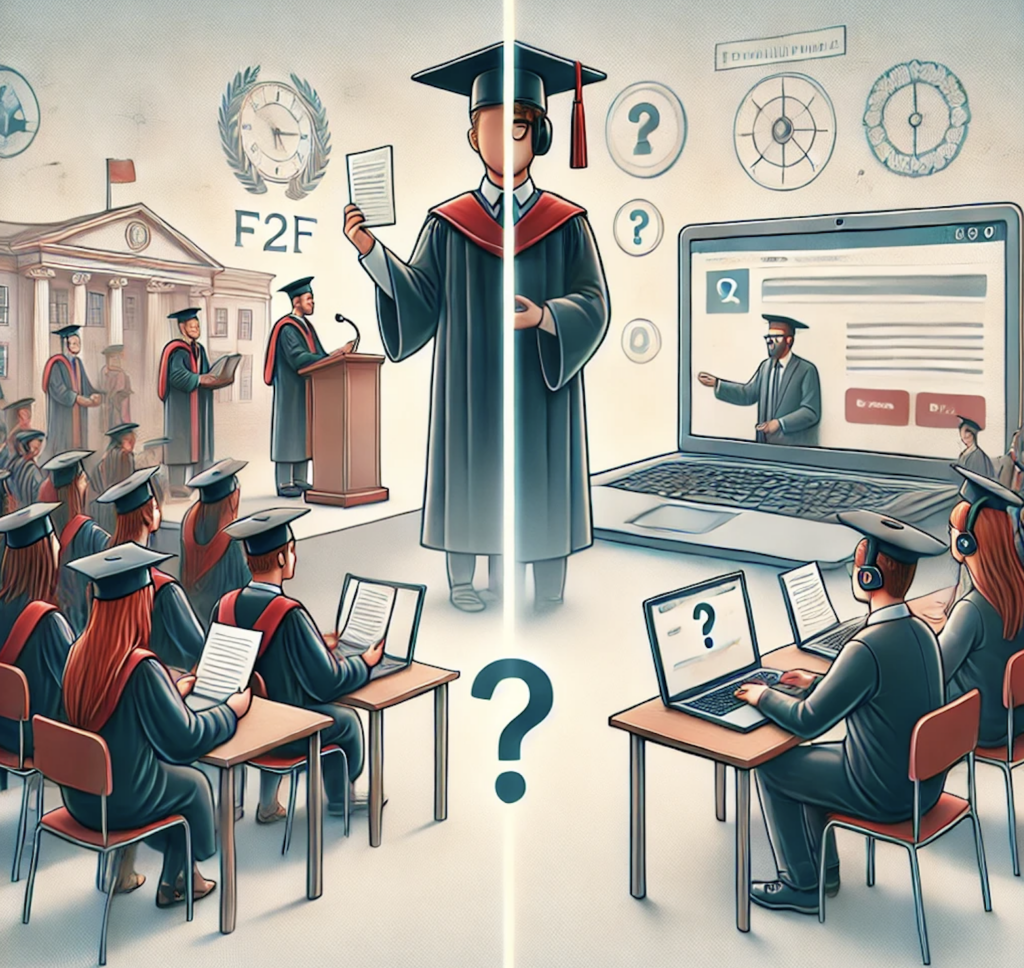

A few weeks ago, an interesting debate unfolded on LinkedIn about whether degrees completed online should have ‘online’ written on the certificate. The idea behind it seemed to be about distinguishing online and face-to-face (F2F) degrees—apparently so employers could decide which ones they could trust more when hiring. The discussion originally stemmed from a closed-door dialogue held among some higher education leaders in Australia. Funny enough, it reminded me of a similar debate I was part of a decade ago in the Maldives.